The Standard Model and Beyond

This post shall concern probably the biggest question in Science that dates back to almost 2500 years in the ancient Greek philosophies. The question is quite simple: What are we made of? What is everything in this observable universe made of? What are the fundamental building blocks of everything we see around us? Although the question might decisively look simple, but the answer to it isn't. What I shall try in here is to just put an overview of where we are in our current understanding of what might be a possible answer to this question, and where we hope to go in the near future.

Its quite a customary thing now to start a writeup that 'answers' these questions to start from what the ancient Greeks said about atoms and how we have come accross several discoveries to understand where we stand now. But here I won't bore you with these historical insights, rather start with something that might be more interesting and more connected to our modern understanding of these questions. A better place to kick start such a discussion is probably the 'periodic table of elements' that harbours all elements that makes up everything we see around us. So any material we get we can distill it down to its component parts and we shall find all of its components is made of these 118ish blocks in the table. This was what was the vectorian view of what matter is made of.

/PeriodicTableoftheElements-5c3648e546e0fb0001ba3a0a.jpg) This was probably one of the triumphs of science, and the reason why most people stop doing chemistry in high school. Kidding!

This was probably one of the triumphs of science, and the reason why most people stop doing chemistry in high school. Kidding!

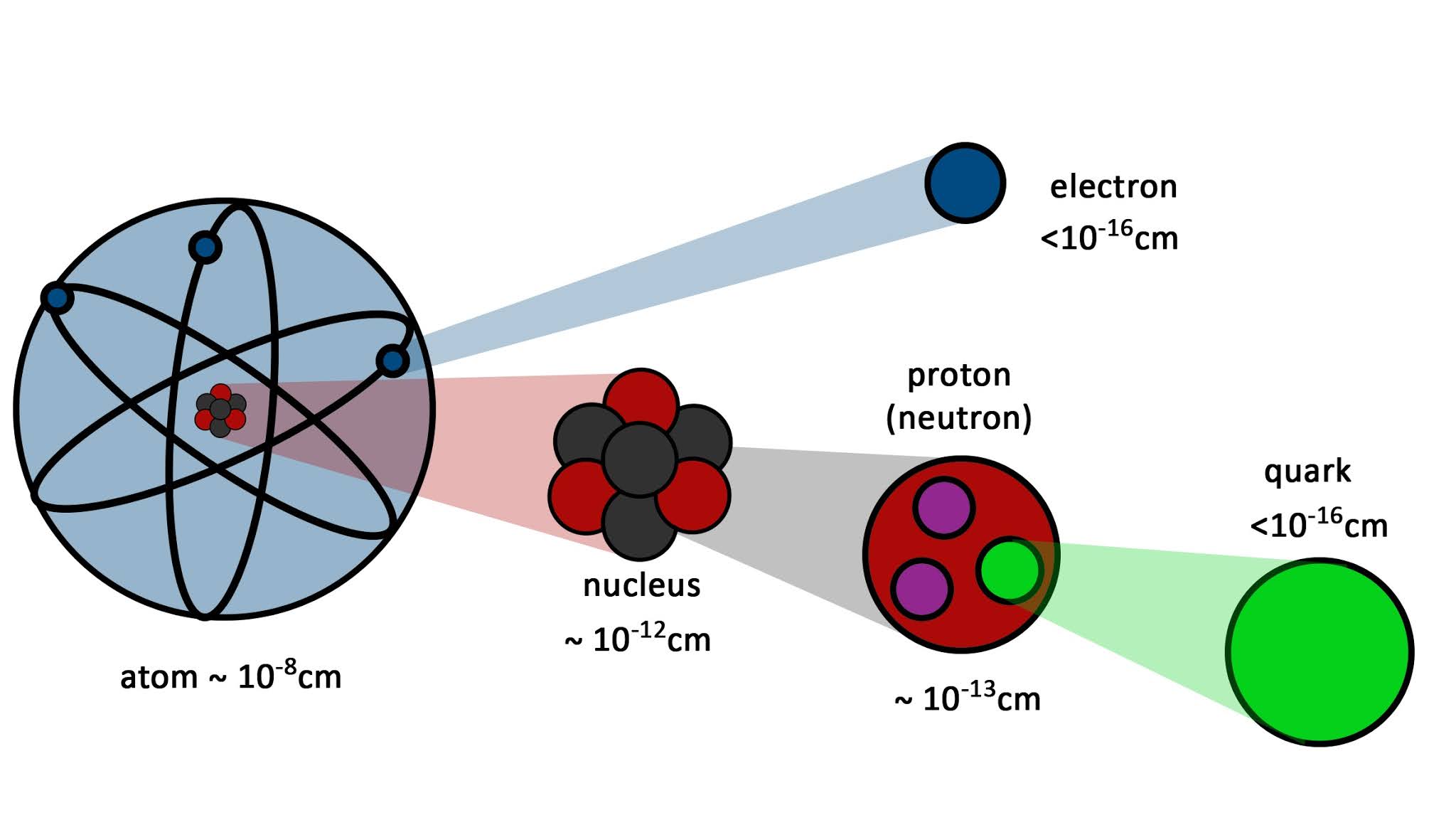

But it is still a mess, the particles to the left in red are the ones that when put in water/air explodes, whereas the ones to the right the purple boxes pretty much donot react to anything! And the story gets worse and worse by the time we reach the bottom most pannel separated out called the Lanthanides and the Actinides. Nature doesnot look quite this way. This isn't the fundamental building block of nature. And, the first person to realise this was a physicist called J.J Thomson by the end of 1800s when he discovered a particle smaller than the atom, called the electron. Within next 15 years of this discovery, Ernest Rutherford had already figured out what these atoms are actually made of. So each of these blocks, the elements in the periodic table consists of a nucleus which is 'tiny' and orbiting this nucleus in 'blurry' orbits move the electron filling sparsely the rest of the space. Subsequently we learnt that the nucleus is not itself fundamental and are made of neutrons and protons, and by the early 1960s we learnt that these protons and neutrons aren't fundamental either. Inside each proton and neutron are three smaller particles called 'quarks' that came in two types: the 'up quark' and the 'down quark'.

A proton is made of a down quark and two up quarks, and the neutron is made of two down quarks and an up quark. These as far as we know are the fundamental building blocks of nature. We have never discovered anything smaller than the electron or these quarks. So we have three particle of which everything we know is made. Its astonishing! Isn't it?

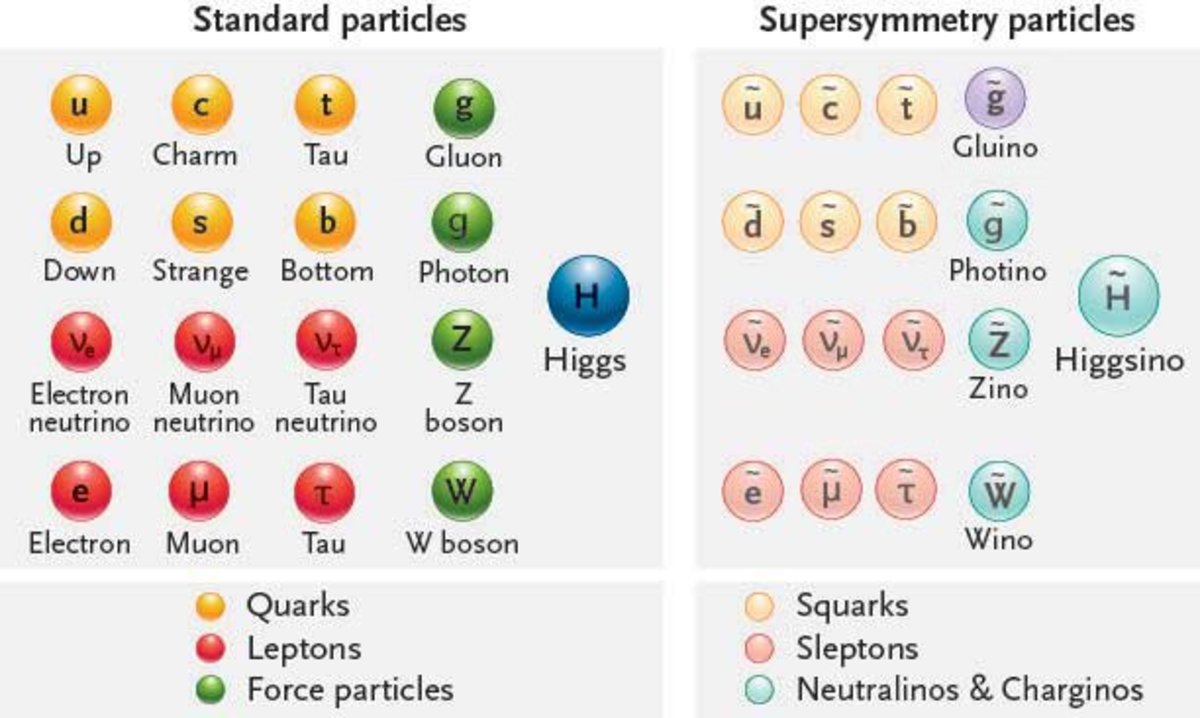

This was the starting point of what we call the Standard Model of Particle Physics. It is what we have the closest till now to describe the universe to its fundamental level. And then what gets added up to these is the 'neutrino'. They are like ghosts that are really undetectable particles, trillions of which move past us that are produced by the sun in vast quantities. They very very rarely interact with the ordinary matter we are made out of. This pretty much makes up for what we call the 'first generation' of matter. Now for reasons that we donot still very well understand, nature provides us with two additional copies of each of these first generation matter particles. Now these are just heavier sibblings of them and are unstable, but are same in all other aspects. That makes up the second and the third generations of matter particles. And the reason we are not made of say a muon, a heavier sibbling of the electron is because it will decay very quickly into an electron and some neutrinos. But these can for sure be made in high energy collisions, like say at the LHC. These 12- particles is what makes up all matter in the universe. They are all collectively known as the fermions.

But why do we have three and just three generations of matter particles is what is a mystery. There must be a deeper structure that can explain this. Maybe I can come back to it after a while.

The last ingredients of the standard model are the force particles: for the three fundamental forces- the electromagnetic force carried by the photon, the strong interaction by the gluon and the weak interaction by the two W and a Z-boson.

This completes the the modern description of the Standard Model, the fundamental picture of what we all see around us. This was the standard model as was known and studied till the 3rd of July 2012. And in the 4th of July 2012 was discovered the Higgs, the last piece of standard model, that is known to give mass to the other particles in the table.

But as good as it seems its not true and a very satisfactory picture! As surprising as it might seem, but the best theories we have in physics donot rely on existence of 'particles' as the fundamental building blocks of nature. The best theories of physics tell us that the fundamental building blocks of nature are not particles, rather are much more abstract, and fluid and nebulous, what we better know as fields. These are fluid like substances that spread all across the universe and ripple in interesting and strange ways. That is the fundamental reality we live in. Now a physicist's description of a field is quite different. It is something that takes a particular value everywhere in space, and can fluctuate in time. It might seem really dubious and strange, but if we think of it a bit on a historical perspective, we'll know it is something we have come across almost 200 years ago with Michael Faraday demonstrating how when two similar poles of a magnet is brought close, we feel something that pushes away, something that is like a fluid, and with sbsequent contributions and discoveries from other scientists it was better known as the Electromagnetic field. This was probably one of the most revolutionary abstract idea in the history of science.

It took us almost 150 years to appreciate Faradays idea of electromagnetic field. And what happened in these years was a small revolution in science. In these years we realised that the world is a very different reality than what we have inherited from Newton's and Galileo's ideas about the universe. In 1920s Schrodinger and Heisenberg and their contemporaries realised that on the smallest scales, the world is much more mysterious and counter-intuitive than we ever realised it to be. It is the theory that we now know as the Quatum Mechanics. Speaking of quantum mechanics, its a major discipline in its own right but let me summarise the basic finding we get from it: "Energy is not continuous, rather parcelled up in little lumps and packages, we called quanta". The real fun comes when we combine the ideas of quantum mechanics with Faraday's ideas of fields which are very much continuous in space. This is what we call the Quantum Field Theory. The first implication is what happens to the electromagnetic field? Faraday taught us and Maxwell later that the waves of the Electromagnetic field are what we call 'light'. But when we marry quantum mechanics to this we see that these light waves aren't quite smooth and continuous as they appeared. They are made up of little lumps or packets of energy that we call the 'photon', and this is where it all started. The magic of this idea is that it applies to every single particle in the universe. So the particles that we see in the standard model of particle physics is nothing but little packages of energy in the their respective fields. Like for example we have everywhere spread around us say this electron field, and the ripples or the waves of this electron field gets tied into little bundles of energy by the rules of quantum mechanics, and these are what we called the particles, electrons. But this is a really really hard problem. To appreciate this, let us consider we take a chunk of space and take off all particles that exist in there. All atoms and electrons and nucleus, everything. What lives behind is just the fields that fluctuates in time across the entire chunk space obeying the Heisenberg's uncertainty principles, and this is what such a vaccum fluctuation looks like:

And this is what 'nothing' looks like, so what goes further more a single particle is a lot more complicated than this, and this goes on! I won't go into much of a detail in here.

So the world we live in is a combination of these sixteen fields, interacting amongst themselves. Say one of the matter fields, the electron field starts to ripple up and down (there is an electron there), this can kick off one of the other fields. It will kick off say the electromagnetic field, which in turn will oscillate and ripple, that might interact with the quark field and that will start to ripple. So the picture we end up with is this harmonius movements between these fields interlocking each other, this is the picture that we have of the fundamental laws of physics. It is the Pinacle of Science, with ironically the most mundane name, 'The Standard model'.

But what about the Higgs field? Its the field that gives mass to the other particles. It is the interaction of the particles with the Higgs field that gives it its mass, just like an interaction of a particle with the lectromagnetic field gives it its charge. The existence of this Higgs field was predicted by a physicist Peter Higgs, who in 1964 along with five other scientists proposed the Higgs mechanism to explain why some particles have mass. Peter Higgs predicted that if we can excite this Higgs field high enough, we can get ripple in a Higgs field, the quanta of the field that is called the Higgs boson. In July 4th 2012, almost 50 years after the theoretical prediction, we finally discovered the Higgs boson at CERN, Geneva. Now, Higgs has its own story to tell, which we will discuss in a future blog!

So, coming back to our discussion, this is all we see around us. This is what tells us about every single experiment of science, everything we see around us. This is our current understanding of what the universe is like and a theory close to the theory of everything!

So what beyond?

Although the standard model gives us results with some exceptional level of precision that matches our experimental findings, it doesn't come without a problem. There are some problems in this too! And, these problems have motivated the building of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Geneva. So lets get into understanding where some of these problems lie.From the astronomical observations of gravitational lensing and rotation curves of galaxies, it becomes clear to us that we donot see as much matter that is present in the universe. This is actually what we call 'The Dark Matter', matter which we cannot see. From observations like these it is possible to calculate the percentage of Dark matter present in our universe.

Computer simulations show that if we donot put as much dark matter, then we donot get the universe we currently live in. But the standard model doesnot give us a particle or a field that can make up for the properties that dark matter shows! What's more surprising is Ordinary matter and dark matter together comprise only about 32% of all the matter, and the rest 68% is Dark energy", about which we are all the more clueless. It is some kind of a mysterious repulsive force acting against the gravitational attraction that causes the universe to expand at an incresing rate. So we have a really great theory that works only in a very narrow domain of only 5% of all that is present in our universe.

Another thing that is important is about antimatter. So, if we look into the standard model (the table that we came across, comprising of all the fundamental particles), we see that there are matter particle called the fermions to the left of this table, each of which is a quanta of their respective fields. Now, for each of these particles, there is sort of a mirror image particle. The discovery of antiparticles dates back to 1930s when it was discovered by Paul Dirac as a 'negative energy solutions' to what we famously know as the 'Dirac Equation'. Positron (the anti-particle of the electron) was later discovered in an experiment by Carl Anderson. The anti particle of each particle in the standard model have all the same properties, except for the electric charge being other way around. Eg: the antiparticle of an electron is called a positron with all the properties same as that of electron, except for a charge of +1. But this is not a problem, since our standard model harbours these anti-particles too. The real problem that comes in now is as follows: If we naively apply this sort of understanding of matter anti matter to the formation of the universe, then this is what happens:

At the big bang we have a huge amount of energy that gets converted into matter and anti-matter pair. Now, as they are being created they are bumping back into each other, annhilating and turning back into light.Now, as the universe expands and cools down, what we are left with is a cold dark place with a few photons wiggling through. However, this is not what the universe looks like. So there must be some kind of process by which we can allow a liitle bit more matter to survive this cosmic annhilation in the beginning of the universe. If we work out it turns out that this imbalance has to be very very tiny. It turns out we are one billionth left over of a much larger stuff that was present in the beginning. But we donot know, how this billionth survived! This is better known as the 'Matter -Antimatter Assymmetry problem'.

These are two of the major problems out of quite some more intricate ones that we can probably know about in a later post that the Standard Model doesn't give an answer to. There are many theories to explain these that are possible extensions of the standard model. But one of the most promising idea is what we know as the Supersymmetry! The idea of Supersymmetry is to invoke a new kind of symmetry in nature, rather an odd kind of symmetry and not like the mirror symmetry that we talked about while discussing anti-matter. In supersymmetry we have a symmetry in between the matter particles (the fermions), and the force particles (bosons). What it means is Supersymmetry tells us every matter particle gets a force particle partner, and every force particle gets a matter particle partner. So we end up with an extra table that looks like this:

The interest of SUSY began in the 1980s, and has stayed the most popular extension of the standard model till date. This is because it is very very good at solving some of the problems I tried to discuss in here. The lightest of all sparticles (a SUSY particle) is thought to be a very good 'dark matter candidate'. There are a lot of promising feautures that SUSY offers us as an extension to the Standard Model, but signature of SUSY hasn't been confirmed in any of the experiments at CERN or any other particle collider around the globe till date. But there are multiple hints indicating towards something spooky going on, but there are no confirmations to these. This brings us to the end of the story of what our current understanding of what everything is at its fundamental level in form of the Standard Model of particle physics and well... a hint to where we intend to go with these in our near future explaining more darker realms and more fundamental questions yet unanswered!